After the attack on the Kerch Bridge, who will be the Real Winner of the Russo-Ukrainian War? asks William Kelly

On Saturday we woke to the news of a catastrophic explosion on Kerch Bridge in Crimea, engulfing a passing freight train and partially damaging its roadway. It has since been suggested that it was an attack by Ukrainian Special Forces, even though Kyiv has so far denied direct responsibility. They did however claim that it was an attack of colossal significance, and they are undoubtedly correct about this. Despite Russia’s claims of repairing the damage and resuming the flow of traffic, the fact that such a disruption took place means supplies can no longer be reliably delivered to Russian troops in Southern Ukraine. More importantly at long last the war is returning to the very place where it started – Crimea.

It’s perfectly understandable why the Ukrainians are positively giddy over the event, as while the situation still remains fluid, the return of its lost lands and an end to this sad affair could well be in sight.

Of course we shouldn’t regard the war as being won – Vladimir Putin could still escalate this conflict to a nuclear level but – since I have all faith in the Russian Oligarchs’ and people’s ability to remove Putin from power – I believe we can expect a peaceful resolution to this conflict, whether Putin desires to or not. While some will say planning for an end to the conflict now is premature, I say it is about being prudent, especially when we consider how woefully ill-prepared Britain and the other Western Democracies are compared to the other powers involved. Namely we have yet to ask ourselves the fundamental question of this whole conflict, which is – what do we want? We’ve flown Ukrainian flags, shouted ‘Slava Ukraini’ and that Vladimir Putin must be stopped, but we haven’t yet discussed what we want after the war. Do we wish for Ukraine to become a full member of the Western Alliance? Do we want Russia to be shattered and punished for its crimes? Or do we in fact not want anything and just simply wish to defend those in need? These questions need to be answered not just for their consequences but also for the fact that other powers that do not share our democratic point of view have already answered them.

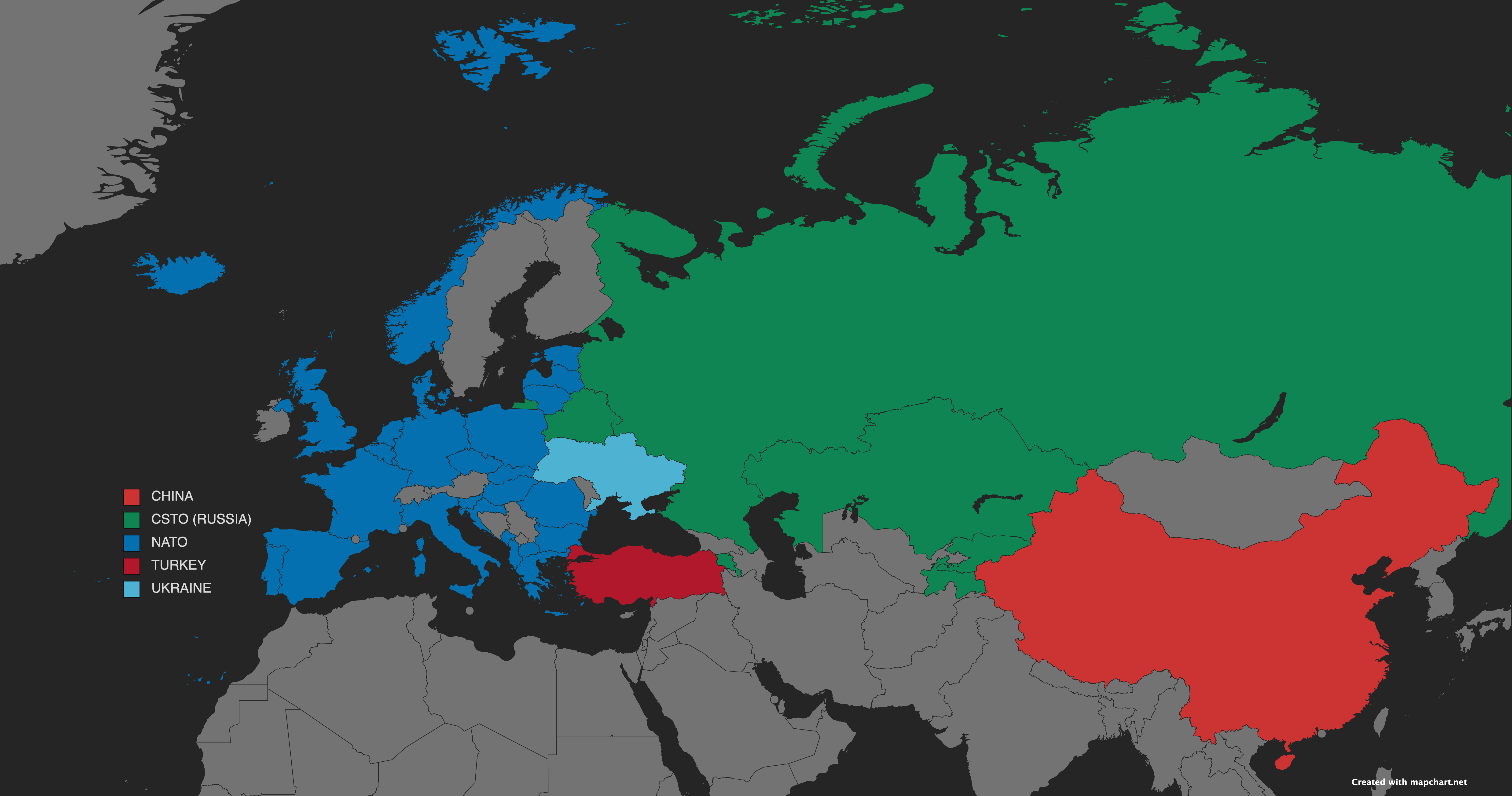

The consequences of a weakened Russia seem wonderful to the majority of the world – especially to the Ukrainians. A neutered Russia would be unable to undermine the sovereignty of its neighbours and eliminate what has been a persistent threat to European stability and democracy. Yet such a Russia would then be unable to retain its sphere of influence and perhaps even its own territorial integrity. We have already seen members of the CSTO like Kazakhstan in January of 2022 waver in just the face of minor Russian setbacks, so it’s not unreasonable to expect other members to leave Russia’s sphere and look to other powers to guarantee their security. China in particular would benefit tremendously from a weakened Russia, not only able to supplant its role in Central Asia, but also being able to extend its economic and political influence as far as the Urals. The uncomfortable truth is that Vladimir Putin is the only thing standing in the way of Russia becoming a Chinese puppet state.

Another important matter is who will actually mediate negotiations between Ukraine and Russia for, in the initial shock of the invasion, the West had lost two of its greatest diplomatic powers – Sweden and Finland. The Russian invasion naturally caused many countries to re-evaluate their own security policies, with Sweden and Finland taking the most radical steps officially applying to join NATO in May of this year. However, I would argue we had lost more than we had gained in these newfound allies, simply because they already were before they had joined NATO. Sweden and Finland did maintain an official policy of neutrality, which made them an ideal mediator, but because they were liberal democracies we could rely on them to push our interests despite their neutral position. Finland was at the forefront of this, facilitating the negotiations between the US and USSR ushering in the era of Detente, with Urho Kekkonen the longest-serving president of Finland becoming the primary architect of Europe’s modern geopolitical and security structures. Not to mention Sweden and Finland were already protected by the EU’s equivalent defence agreement (Article 42), a security guarantee the likes of Ireland and Austria don’t see a need to be supplanted by NATO protection. Of course everything’s changed now, with mediation between Russia and Ukraine now seemingly being carried out by Turkey, which is a problem we should all be concerned about.

Specifically, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has positioned Turkey as the primary diplomatic arbiter of the Ukrainian conflict, with his most recent triumph the reopening of Russian and Ukrainian agricultural exports through the Bosporus, avoiding a global famine. Erdogan has achieved this despite the fact that Turkey is both a full member of NATO and closely linked to the EU. But this isn’t due to his diplomatic skill or reputation, rather it’s the product of a long-standing sympathy between Erdogan and Putin. For Erdogan is an authoritarian; he has cracked down on dissident journalist, he has rewritten Turkey’s constitution to monopolise power and torn up Ataturk’s legacy of a secular state – sound familiar? Erdogan has also consistently acted against the interests of the West; from using the release of migrants in Turkey to blackmail the EU of funds, brinkmanship diplomacy with the US in order to crush an emerging Kurdish democracy and Western ally in Syria, the supporting of Azerbaijan in their conflict with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh and direct provocation against France and Greece in the Aegean. As you can see, Erdogan has been more of a enemy to the West than Putin has, and it’s for this reason why Russia and Turkey have enjoyed if not a warm relationship, then certainly mutually beneficial one.

This war will end. The guns will fall silent. The soldiers will come home. But whether peace will come is another matter entirely. The fate of Eastern Europe and West Asia are now hanging in the balance, but not such much on who will win the war, but who will win the peace. Will Russia be humiliated a second time and fall into internal instability? Will Ukraine persevere and assert itself as an Eastern European juggernaut? Will China sweep in to pick up the pieces of Putin’s shattered empire? Will Turkey reclaim its Ottoman legacy and become the Caliph once more? All these questions I’m sure will be answered in time, but there is one matter I am sure of and it is our own neglect of duty to the good and free of this world. We have resolutely stood by Ukraine in the face of unprovoked aggression and offered them our aid, but to what end? Ukraine may have begun the process of joining the EU, but the Commission in Brussels has no intention of welcoming in another illiberal democracy like Poland or Hungary, which Ukraine still is. President Zelensky may have applied for NATO membership, but he should look to Georgia’s own NATO aspirations and see how willing the West is to change the balance of power, and if anything that’s the problem.

The Russo-Ukraine War is a conflict born out of 30 years of inactivity by a successive generation of Western politician who have been clinging to the world that no longer exists. It wouldn’t surprise me if the aim of leaders in Washington, London or Brussels is to return Russia to its 1990s pre-Putin state, a Russia it can continue to sell Bentleys or any other mass consumer product to, which granted would be better than the current state of affairs. But while we may endeavour to continue living in the past, be sure that other nations are not; if we continue to resist the future we will find ourselves written out of it. For other nations will work to ensure that they are the victors and that their ideology or interests rule – the only question is whether we are willing to do the same?

Pic: (L-R) Xi Jingping, China, Vladimir Putin, Russia and Recep Tayyip Erdogan, Turkey.

William Kelly works for The Catholic Network, and is a student of Politics and International Relations at Liverpool Hope University.